When I was 20 I took a long trip on foot over mountain heights unknown to tourists through the ancient region where the Alps thrust down into Provence (south-east France). At the time I embarked, these deserted regions were a barren and colourless land. Nothing grew but wild lavender.

After three days walking, I found myself amid unparalleled desolation, camped near the vestiges of an abandoned village. I had run out of water the day before and was desperate to find some. The six roofless houses would offer no shelter, and the spring that was here had run dry. I had to move on.

Five more hours and I had still not found water, and there was nothing to give me any hope of finding any. All about me was the same dryness, the same coarse grasses. I glimpsed in the distance a small black silhouette, upright, and took it for the trunk of a solitary tree. As I drew closer, I saw it was a shepherd and with him thirty sheep were lying around him on the baking earth.

He gave me a drink from his gourd and a little later, took me to his cottage. He drew his water from a very deep natural well, above which he had constructed a primitive winch. The man spoke little. His dwelling was built of stone, bearing evidence of how his efforts had reclaimed the ruin he had found. His roof was strong and sound. The place was in order, the dishes washed, the floor swept, his rifle oiled; his soup was boiling over the fire.

There were four or five villages scattered well apart from each other on these mountain slopes, the ends of the wagon roads. They were inhabited by charcoal-burners, and the living was bad. Families crowded together in a climate that was excessively harsh both in winter and summer and they found no escape from the unceasing conflict of personality. The men took their loads of charcoal to the town, returning at the end of the day. The nature of these villages was rivalry in everything - over the price of charcoal as over a pew in the church. Over all things, there was a harsh, ceaseless wind that rasped upon the nerves. The soundest characters broke under the perpetual grind of life here; there were epidemics of suicide and frequent cases of insanity.

The shepherd went to fetch a small sack and poured out a heap of acorns on the table. He began to inspect them, one by one, with great concentration, separating the good from the bad. When he had a large enough pile of good acorns, he counted them out by tens, eliminating the small ones or those which were slightly cracked, examining them more closely now. When he had selected a hundred perfect acorns, he went to bed.

There was peace in being with this man. The next day I asked if I might rest here for a day – I did not truly need to rest but I wanted to know more about this fascinating shepherd. He opened the pen and led his flocks to pasture but not before plunging his sack of precious acorns into a pail of water.

He left the little flock in a pasture in the valley, under the watchful eye of his dog. He then climbed the nearby ridge and began thrusting his iron rod into the earth, planted acorns and then refilled the holes. He supposed it was community property, or perhaps belonged to people who cared nothing about it. Either way, it was not his land but he planted his acorns with the greatest care, unperturbed.

He resumed planting after lunch, telling me he had been doing this for three years, planting around 100,000 acorns in this time. Of these, 20,000 had sprouted. Of the 20,000, he expected to lose about half to rodents or to the unpredictable designs of Providence. Thus remained 10,000 oak trees to grow where nothing had grown before.

That was when I began to wonder about the age of this man. Fifty-five, he told me, along with his name; Elzéard Bouffier. He had once had a farm in the lowlands which had been his life, until he lost his only son, then his wife. He opined that the land was dying for lack of trees and, having no pressing business of his own, resolved to remedy this.

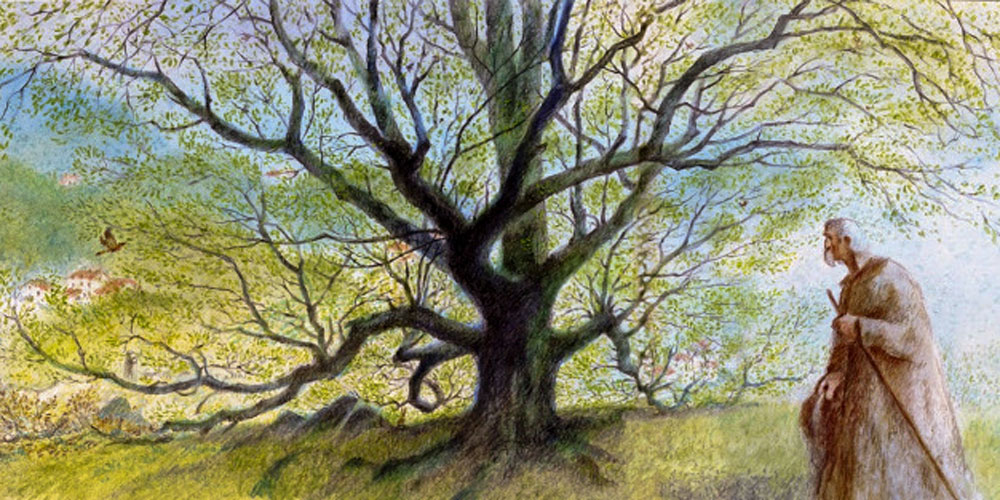

Elzéard goes about his simple buisness, planting trees.

Elzéard goes about his simple buisness, planting trees.

The next day we parted. The following year came the War of 1914, in which I was involved for the next five years. An infantryman had no time for reflecting upon trees but, to tell the truth, the thing had made no impression upon me; I had considered the whole effort as a mere hobby. When the war ended, I found myself equipped with a tiny demobilisation bonus and a huge desire to breathe fresh air for a while. This was the only reason I returned to the barren lands and I saw that the countryside had not changed. However, far beyond the deserted village, I glimpsed a greyish shape that covered the mountaintops like a carpet.

“Ten thousand oaks”, I reflected, “really take up quite a bit of space.” I had seen too many men die during those five years not to imagine that Elzéard was among them. Rather, he was extremely spry with just four sheep and, instead, a hundred beehives. He had got rid of the sheep because they threatened his young trees. The war had disturbed him not at all.

The oaks of 1910 were now 10 years old and taller than either of us. It was an impressive spectacle that measured 11 kilometres in length and three kilometres in width. The efforts of one set of hands with no technical resources showed me at least some proof that men could be as effectual as God in realms other than that of destruction. Creation had returned as a chain reaction - I saw water flowing in brooks that had been dry for an age.

The wind, too, scattered seeds. As the water reappeared, so did willows, rushes, meadows, gardens, flowers, and a certain purpose in being alive. But the transformation took place so gradually that it did not cause any great astonishment. Hunters, climbing into the wilderness in pursuit of hares or wild boar, had noticed the sudden growth of trees but had attributed it to some caprice of the earth. No one meddled with Elzéard’s work as no one knew it was happening. Who in government could have dreamed of such perseverance of magnificent generosity?

In 1933, he received a visit from a forest ranger who notified him of an order against lighting fires for fear of endangering the growth of this “natural forest”. At that time Bouffier was about to plant beeches at a spot some 12 kilometres from his cottage. In 1935, a highly official delegation came from the Government to examine the "natural forest". They decided that the forest would be placed under the protection of the State and charcoal burning prohibited. It was impossible not to be captivated by the beauty of those young trees in the fullness of health.

The natural beauty of a forest is a truly special sight to behold

The natural beauty of a forest is a truly special sight to behold

An old friend of mine was among the forestry officers of the delegation. I explained the mystery to him and we visited Elzéard together, finding him at work ten kilometres from his cottage. Peaceful, regular toil, the vigorous mountain air, frugality and, above all, serenity in the spirit had endowed this old man with awe-inspiring health. He was one of God's athletes. I wondered how many more acres he was going to cover with trees.

My friend made a brief suggestion about certain species of trees that the soil here seemed particularly suited for. He did not force the point, "for the very good reason that Bouffier knows more about it than I do". Later, he added, "He knows a lot more about it than anybody. He's discovered a wonderful way to be happy!" It was thanks to this officer that not only the forest but also the happiness of the man was protected.

This great tree-shepherd and his growing herd avoided the impacts of the war of 1939; as the area was so far from any railway, any enterprise was financially unsound. I saw Elzéard Bouffier for the last time in June of 1945 when he was then 87. On my way I passed through a hamlet that in 1913 consisted of 10 or 12 houses and three inhabitants. They had been savage creatures, hating one another, living off trapping game, physically and morally resembling the conditions of prehistoric man. Their condition had been beyond hope; there was nothing for them other than to await death.

Everything was changed. The harsh, dry winds were gone, replaced by a gentle breeze, laden with scents. I heard the actual sound of water falling into a pool - a fountain that flowed freely had been built. On the site of the ruins I had seen in 1913 now stood neat farms, cleanly plastered. The old streams, fed by the rains and snows that the forest conserved, flowed once more. Little by little the villages had been rebuilt.

People from the plains, where land is costly, have re-settled here, bringing youth, motion and the spirit of adventure. Along the roads travel hearty men and women, boys and girls who understand laughter and have recovered a taste for picnics. Counting the former population, unrecognizable now that they live in comfort, more than 10,000 people owe their happiness to EIzeard Bouffier.

When I reflect that one man, armed only with his own physical and moral resources, was able to cause this land of Canaan to spring from the wasteland, I am convinced that, in spite of everything, humanity is admirable. But when I consider the unfailing greatness of spirit and the tenacity that it must have taken to achieve this result, I am taken with an immense respect for that old and unlearned peasant who was able to complete a work worthy of God.

Taken from the 2021 Autumn edition of the Salesian bulletin, which is available now!